A historical study of the evolution of the definition and rules regulating media presence at the Olympics in the Olympic Charter from 1908 to 2011

– a conference paper presented at I Congress on History and Sport, anemia May 31-June 1, steroids 2012, Lisbon, Portugal –

On the 1st of June, I had the opportunity to present a paper at the I Congress on History and Sport in Lisbon, based on primary research undertaken for my PhD and made possible thanks to a IOC Postgraduate Research grant. The paper focused on changes in the Olympic Charter regarding media from the 1st edition of the charter to the current one.

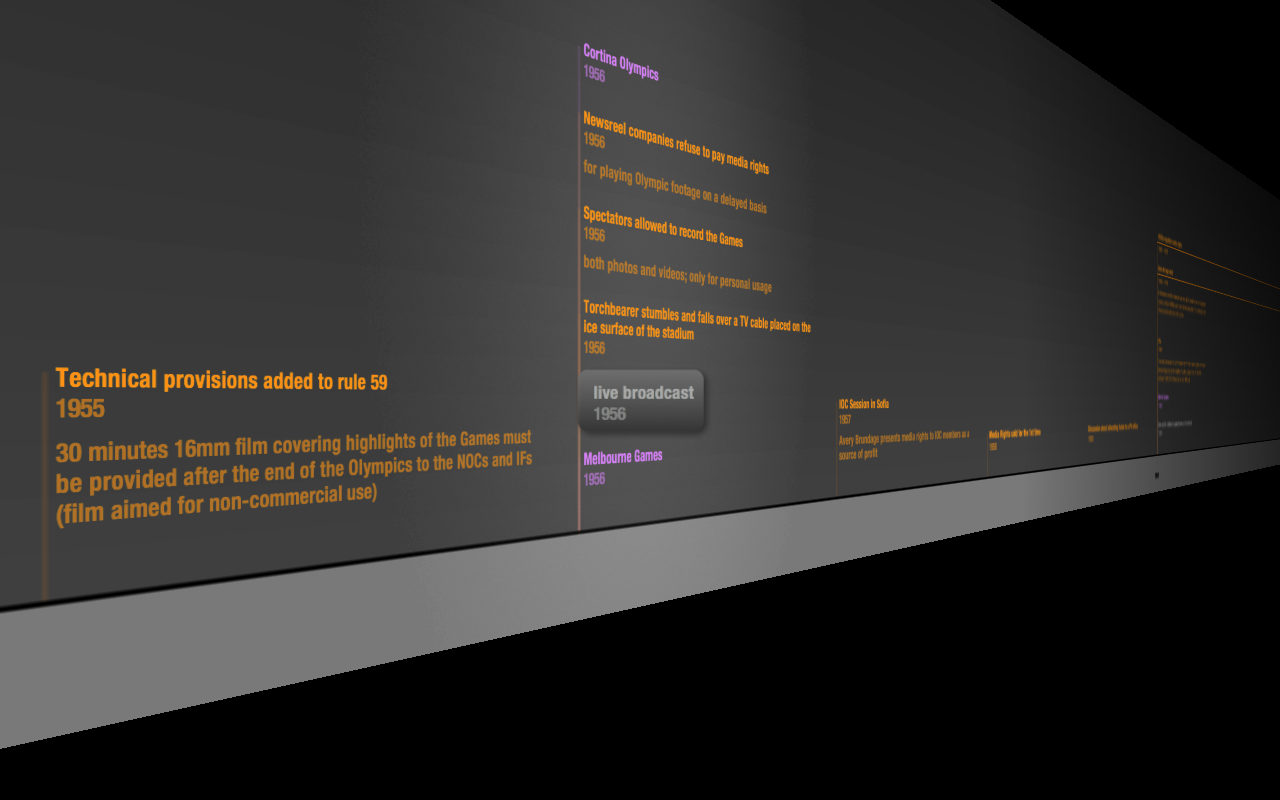

Unlike the last time when I presented a timeline project based on research of the Charter – Fundamental principles of Olympism: a mechanism for human rights promotion -Â I used the licensed version of Timeline 3D, a timeline creation software for Mac which enables simple import and imput of data as well as multiple ways of exporting the final result – from online upload, to iTunes and YouTube video or pdf storage.

In displaying the results, I used several color codes: orange for changes in the Charter, gray for media and technology developments and purple for Olympic Games editions. In gathering the data I used the editions of the Olympic Charter but also meetings notes from the IOC Sessions and meetings of the Executive Board of the IOC to which I gained access during my scholarship and grant at the IOC in Lausanne.

There are 3 main conclusions for the study:

1. The “media rule” becomes increasingly specialized with the time

The rule addressing the Olympic Movement’s relationship with media changed from the “Taking of photographs and film pictures†in the 1930s to “Publicity†in the late 1950s, to then “Information media†in the mid1970s and “Mass-Media†in the late 1970s. Other titles included “Mass-Media-Publications-Copyrights†in the early 1980s to “Mass-Media: graphic impression, sound and/or vision recording and electronic broadcasting†in the mid-1980s to “Media Coverage of the Olympic Games†from 1991 onwards. A shift from a technical approach to a more precise approach in the rule is therefore predicted by the title. But perhaps the true intention of the IOC’s words with this rule is best reflected in its 1958-1974 title “publicity†where it posits the IOC as an institution aware of the importance of positive attention and actively seeking it. The current title of the rule, “Media coverage of the Olympic Games†shifts the accent from the sender of the message to the medium, in this case mass-media (Adi, in manuscrips)

2. The “media rule” and its effect are constantly expanded

Not only did the media cover how the media would access the Games but also how it would report from it, how often and how much and what about. Although this last element is not clearly indicated in the rule, indirect mentions to media supporting the Olympics and their ideals suggest that the rules were aiming to influence beyond the time and format of the media coverage.

3. The IOC’s growing power is expressed in tightening controls and more protectionist measures (of the brand, of the Games, of the IOC itself)

(…) the IOC’s increasing power and growing control over the image and look of the Games as well as over negotiation and definition of media rights, media distribution, and communication about and during the Olympics also visible in the media rule changes. Signs of control were first visible in the 1960s as the talks about how the revenue from television rights should be shared. A professionalized approach to communication followed with the IOC’s decision to hire and fund a Public Relations office. As a consequence, the regulatory framework expanded from media rights and access to the stadia, to, among others, access to Olympic events, media roles and their incompatibility with the participating athlete status. This culminated with very explicit formulations of the IOC being the “final authority†in Olympic media related matters, its decision being binding (Adi, manuscript). Â

Implications

The results also bring several questions about the relationship between media and Olympic officials – from the IOC, to organizing committees, sport federations and national olympic committees – and to how the rule has been translated in their own regulations and guidelines. For instance with regards to social media, elements of the media rule and bye-law are currently explained in separate social media guidelines. It would be interesting to compare the regulations between all the Games participants and Games makers.

Furthermore, the results also call attention over definition of media and its perceived role over time as well as into the reinforcement of the rules.

References:

Adi, A (2012) Media Regulations and the Olympic Charter: a history of visible changes.